Global Shipping Decarbonisation: Navigating Towards a Greener Supply Chain

10 mins. read | 15th April 2025

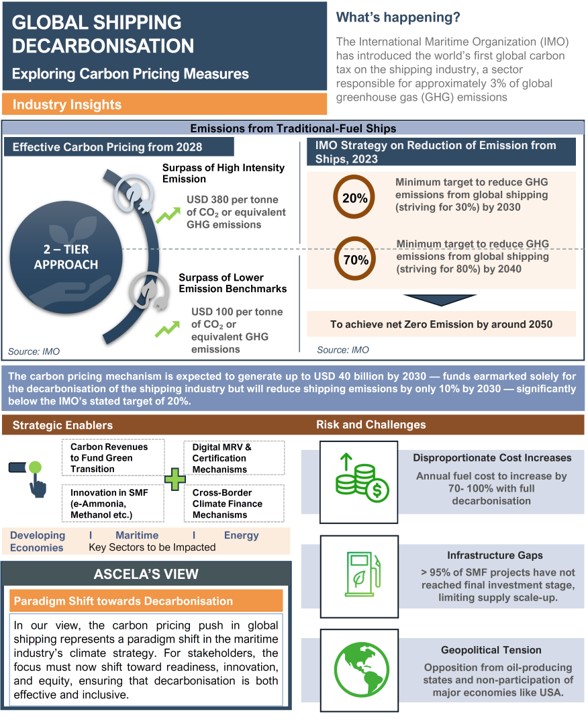

The maritime industry stands at the precipice of a pivotal transformation. In a sector long considered a cornerstone of global trade and economic development, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) has introduced a first-of-its-kind global carbon pricing mechanism, marking a radical departure from conventional maritime operations. As of April 2025, this historic step signals a broader global trend — a paradigm shift towards decarbonisation, placing the shipping industry under the same climate lens that has already begun reshaping power generation, automotive, and manufacturing sectors. With shipping responsible for nearly 3% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, its decarbonisation is no longer optional; it is a moral and strategic imperative for nations and corporations alike.

What does this global carbon tax mean for the industry?

At its core, the IMO’s initiative introduces an effective carbon pricing mechanism beginning in 2028, aimed at placing an economic value on emissions from traditional fuel ships. The proposal introduces a two-tiered approach: USD 100 per tonne of CO₂ or equivalent GHG emissions for low-impact journeys and up to USD 380 per tonne for high-emission voyages. This pricing is not arbitrary.

The proposal is backed by a strategic vision to leverage market mechanisms to influence behaviour — rewarding greener practices and penalising carbon-intensive operations.

According to estimates, this pricing framework could generate up to USD 40 billion by 2030, earmarked exclusively for green transition investments in the maritime sector. While this financial influx offers a potential lifeline for innovation and infrastructure development, concerns remain around its effectiveness and the strategy for fund redistribution among countries, which still needs to be evaluated.

Forecasts suggest the initiative may reduce emissions by only 10% by 2030 — falling short of the IMO’s stated interim target of 20% and long-term aspirations of 70% emission reductions by 2040, en route to net zero shipping by around 2050.

These targets reflect growing pressure from global climate treaties, public sentiment, and investor demands for climate accountability.

However, meeting them will require far more than carbon pricing — it will demand fundamental shifts in ship design, fuels, financing, and governance.

Can carbon revenues truly fund a green shipping transition?

A crucial feature of the IMO’s strategy is how the carbon tax revenue will be channelled. The revenue is not intended to be absorbed into general government treasuries; instead, it will be invested in green transition measures, but what will be the basis for distribution remains the question.

There is a need for investment in the following sectors:

- R&D in sustainable marine fuels (SMFs) such as green ammonia, methanol, and hydrogen

- Digital MRV (Monitoring, Reporting and Verification) and certification systems to validate emissions reductions

- Cross-border climate finance mechanisms to enable equitable access to technology, especially for developing economies

This highlights a critical question: Is the sector ready to rapidly scale these solutions?

As of early 2025, more than 95% of SMF projects have not reached the Final Investment Decision (FID) stage, suggesting a significant infrastructure gap. While pilot projects in Norway, Japan, and the Netherlands demonstrate promise, the industry’s capacity to translate pilot success into commercial-scale deployment remains limited. Without large-scale, accessible infrastructure, shipping companies face a “chicken-and-egg” dilemma — hesitant to invest in green ships due to uncertain fuel availability and fuel suppliers unwilling to scale without assured demand.

Strategic Enablers

To accelerate decarbonisation, three primary enablers must converge:

Carbon Revenues to Fund Green Transition

Carbon pricing must be seen not just as a punitive measure but as an investment engine. The redistribution of revenues into public-private partnerships for alternative fuels and port electrification can create market confidence. For example, in Singapore and the UAE, where green port initiatives are already underway, carbon revenue could scale nascent fuel ecosystems rapidly.

Digital MRV and Certification Mechanisms

Accurate emissions monitoring is key to trust and verification. Standardised digital MRV systems will ensure fair implementation of the pricing scheme and help ships demonstrate compliance. These systems must be universally interoperable to avoid regulatory fragmentation across jurisdictions.

Cross-Border Climate Finance Mechanisms

Developing countries — particularly those dependent on maritime exports — face disproportionate costs in the green transition. Financing tools such as green bonds, concessional loans, and blended finance from multilateral institutions will be essential to level the playing field.

These enablers reflect the multi-sectoral nature of the shipping ecosystem. Not only will maritime operators be affected, but so will port authorities, logistics firms, fuel producers, and energy regulators. This makes shipping decarbonisation one of the most interdisciplinary challenges in the energy transition landscape.

Risks and Challenges

Despite its ambitious goals, the IMO’s carbon pricing strategy is not without criticism or challenge. Several risks threaten to stall progress.

Disproportionate cost increases

A major concern across the industry is the expected rise in operational costs. According to estimates, full decarbonisation could increase annual fuel costs by 70-100%. This is especially daunting for operators with thin margins, such as small regional shippers and carriers in developing economies. The question arises: Will these costs be absorbed or passed on to consumers through higher shipping rates and commodity prices?

The concern is not unfounded. With the global supply chain still recovering from disruptions caused by COVID-19 and geopolitical tensions, sudden cost spikes in shipping could exacerbate inflation and disrupt trade flows.

Infrastructure gaps

Infrastructure — particularly SMF availability, port retrofits, and bunkering — remains a major bottleneck. Few global ports are equipped to handle green ammonia or hydrogen bunkering. While leading economies like Japan, the Netherlands, and Australia are advancing, others remain underprepared, especially in Africa, Southeast Asia, and Latin America. This risks creating a two-speed transition, where only certain corridors (like Asia-Europe) are green-ready, leaving the rest behind.

Geopolitical tensions

The carbon pricing mechanism faces resistance from oil-producing states and non-participation from major economies, notably the United States. This undermines the goal of global uniformity. Disjointed participation could lead to regulatory arbitrage, where operators shift operations to jurisdictions with lax enforcement or no pricing. Coordinated diplomacy and regional alignment — particularly through ASEAN, the African Union, and G20 — will be necessary to avoid this.

Spotlight on Developing Economies: Disproportionate Impact, Unequal Readiness

One of the most contentious aspects of maritime decarbonisation is its impact on developing economies. Nations in Asia, Africa, and Latin America — many of whom are export-driven — risk bearing the brunt of compliance costs without reaping proportional benefits. Their limited access to capital, weak port infrastructure, and dependence on fossil fuels make rapid transition costly and complex.

How can carbon justice be ensured in the shipping transition?

If integrated with IMO mandates, mechanisms like the Loss and Damage Fund under COP27 could provide transitional support to these nations. Furthermore, aligning the IMO’s strategy with UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) — particularly SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure) and SDG 13 (Climate Action) — can drive donor and private funding towards equitable solutions.

The Industry Response: Emerging Innovation and Investment

Despite the hurdles, many maritime players are already on the go. Few global shipping giants have already begun investing in dual-fuel vessels, electric tugboats, and biofuel testing. Ports such as Rotterdam and Hamburg have created green corridors for hydrogen-fuelled shipping lanes. Additionally, start-ups and clean energy innovators are developing modular electrolyser systems and carbon capture technologies for maritime use.

“We are seeing a paradigm shift. IMO’s carbon pricing strategy is to be taken not as a constraint, but as a catalyst for systemic change.”

For stakeholders across the maritime value chain, this transition demands a multifaceted approach that spans infrastructure, technology, policy, and cross-sectoral coordination. A key priority is the proactive investment in alternative fuel infrastructure, particularly in emerging economies where port operations are rapidly expanding. These regions have a unique opportunity to leapfrog into cleaner systems by developing bunkering and storage facilities for green fuels such as ammonia, methanol, and hydrogen. Integrating digital systems for emissions tracking, certification, and operational optimisation is critical alongside physical infrastructure.

Leveraging technologies like IoT-enabled sensors, blockchain for fuel provenance, and AI for route and energy efficiency can enhance transparency and performance. Equally important is the need for strategic collaboration across traditionally siloed sectors — including energy, finance, maritime logistics, and port governance — to co-create robust ecosystems that support the long-term viability of green shipping. This must be underpinned by coherent policy alignment to establish globally harmonised standards, reduce compliance uncertainty, and prevent carbon leakage, which could undermine environmental objectives by shifting emissions to less regulated regions. Finally, the principle of carbon revenue recycling should be central to this transformation, ensuring that revenues generated from carbon pricing mechanisms are reinvested locally to improve fuel accessibility, support capacity-building initiatives, and promote inclusive growth in maritime communities.

The Road Ahead: From Ambition to Action

The IMO’s carbon pricing initiative is more than just a fiscal mechanism — it stands as a powerful signal of accountability, a call to reimagine maritime economics through a sustainable lens, and a catalyst for innovation across the sector. Yet, this initiative marks only the starting point of a long and complex journey. Achieving a truly decarbonised shipping industry will demand the rapid scaling of green fuel supply chains beyond limited pilot projects, bridging the stark disparities in transition readiness between developed and developing nations and forging multilateral consensus on global standards, reporting frameworks, and financing mechanisms. Equally crucial is the need to uphold transparency and ensure traceability in emissions data while safeguarding livelihoods by facilitating just and equitable transitions for communities historically reliant on conventional maritime operations.

As global trade continues to be the backbone of economic growth, the decarbonisation of shipping must be treated as a core climate priority. It’s about reducing emissions and reshaping how nations trade, collaborate, and prepare for a carbon-constrained future. With the right blend of carbon pricing, technology, policy, and cooperation, the maritime industry can anchor itself firmly in the clean energy future.

At ASCELA, we are at the forefront of strategic advisory services, helping businesses navigate the complexities of the green energy transition. Our advisory work across Asia and the Middle East has shown that multi-stakeholder coalitions — involving regulators, shippers, port authorities, and financiers — can significantly accelerate readiness. We advocate for carbon revenue recycling, where funds are reinvested locally to boost fuel accessibility and capacity-building.

As the transition to green shipping accelerates, we actively work with key industry stakeholders to identify logistical pathways for SMF adoption, assess investment risks, and leverage incentives offered under global climate finance mechanisms. This includes scenario planning, cost modelling, and technology due diligence.

At ASCELA, we are committed to empowering this transition. We stand ready to support stakeholders at every stage — from strategy formulation to project implementation — to navigate the seas of sustainable transformation.

ASCELA’s strategic consulting empowers maritime players to optimise the shipping decarbonisation process, helping them scale sustainably while addressing market complexities.

As we look towards 2025 and beyond, we can overcome the existing challenges to build a sustainable and carbon-neutral future with the right mix of global cooperation, targeted investments, and innovative technology.

Author:

Nishtha Saha

Principal Consultant

Strategic Advisory- Mobility and Supply Chain

Share via: